IN THIS CORNER OF THE WORLD (この世界の片隅に) (2016)

Genre: Animation

Director: Sunao Katabuchi

Cast: Non, Yoshimasa Hosoya, Minori Omi, Natsuki Inaba, Daisuke Ono, Megumi Han

Runtime: 2 hrs 10 mins

Rating: PG13 (Brief Nudity)

Released By: Encore Films

Official Website:

Opening Day: 6 July 2017

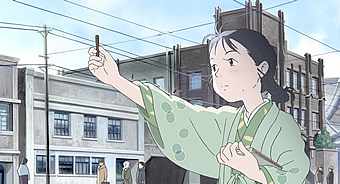

Synopsis: The award-winning story follows a young girl named Suzu Urano (voiced by Non), who in 1944 moves to the small town of Kure in Hiroshima where she marries Shusaku Hojo (voiced by Yoshimasa Hosoya)—a young clerk who works at the local naval base. Living with his family, Suzu learns to adjust to her new life and soon becomes essential to the running of the household during the tough war-stricken climate. Despite the difficult kitchen conditions of wartime regulation, drinking the wisdom of the world, the Hojo family live out their day-to-day lives with Suzu’s creative meals and infectious optimism. The war, however, progresses to ever-growing bleakness. In 1945, intense bombings by the U.S. military finally reach Kure with devastating effect to the townsfolk and their way of life. Suzu’s life is changed irrevocably, and she must now find a way to maintain the will to live.

Movie Review:

‘Your Name’ may have been all the rage in Japan last year, but writer/director Sunao Katabuchi’s crowd-funded adaptation of Fumiyo Kono’s popular manga ‘Kono Sekai no Katasumi ni’ was perhaps even more warmly received by local critics, who bestowed on it numerous awards including Best Japanese Film in the 90th Kinema Junpo Best 10 Award. Both are tonally quite different – whereas the former speaks to the awkwardness of adolescence in its depiction of teenage love and the mysterious hand of fate, the latter harks back to the tragedies of World War II through the coming-of-age tale of an artless, dreamy young woman in the 1940s and strives instead to be thoughtful, restrained and elegiac. In short, you’re not likely to experience or emerge from Katabuchi’s film on an emotional high; in fact, this period anime unfolds on such its own leisurely pace that you’ll need to prepare yourself to settle in fully to appreciate its gentle charms, though we suspect that at slightly over two hours, some will no doubt find their patience duly tested.

Like his previous ‘Mai Mai Miracle’, the lead protagonist Suzu’s tale boasts a similar pastoral tone, although the time period here is about one or two decades earlier. Seven-year-old Suzu is living in Eba, a small seaside town in Hiroshima, with her parents and an older brother and sister. From young, Suzu’s lively sense of imagination is plainly evident; and a scene in her teenage years seals her bond with childhood sweetheart Tetsu through her painting of the sea and its waves as white rabbits, inspired by his description of the ocean. But Suzu’s story really begins at the age of 18 in the year 1944, when she accepts a marriage proposition from Shūsaku from all the way in the naval port city of Kure. Shūsaku remembers meeting Suzu all the way back in December 1933, but Suzu has no recollection of him; notwithstanding, she follows her grandmother’s advice and accepts his proposal, moving in with him and his elderly parents on a hillside in the suburbs of Kure.

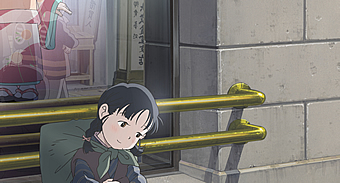

Without any hint of haste, the middle act devotes itself to Suzu’s struggles settling down into her new life of domestication – cooking, fetching water, sewing kimonos, getting fresh produce from the market etc. Given how Suzu has always had her head in the clouds, these responsibilities as a housewife don’t come easy to her, and it doesn’t help that her sister-in-law Keiko, who has moved back along with her daughter Harumi after her husband’s unfortunate death from illness, seems perpetually displeased with her. Slowly but surely, the war makes its effect felt on Suzu as well as on the household: food becomes scarce; essentials like sugar are rationed; the twice-nightly air raids drive the family underground like ritual; and last but not least, Shūsaku as well as her father-in-law Entarō spend more and more time at their posts as a naval clerk and engineer respectively, with the increasingly frequent bombings placing their lives at increasing risk (true enough, Entarō goes missing after the raids hit the Hiro Naval Arsenal, though he is eventually found safe but injured in hospital).

It is at the two-third mark that tragedy strikes. A key character dies in a time-delayed explosion of a bomb dropped during one of the firebombing runs by US naval airplanes; and Suzu’s world withers into a flurry of white lines twisting and fluttering across empty black space. That same explosion also renders her forever incapable of doing the one thing she loves best, i.e. painting. And then the pivotal event happens – the atomic bomb which falls on Hiroshima, erupting in a tremor, a flash, then a huge cloud rising from the ground into the sky, and for a while, Suzu is unable to enter Hiroshima or get any information if her own family was killed in the blast. When the radio broadcasts resume, they are of news of Japan’s surrender, and the sudden ostensible futility of the whole war as well as the costs it had exacted on her bring Suzu to the brink of emotional despair. It is during the third and last act that the movie takes on newfound poignancy, depicting the disillusionment of an ordinary Japanese citizen whose life is thrown into disarray by the terrible monstrosity of war.

But it is also precisely this last third that gets under our skin for the wrong reasons. Certainly, the change in perspective is insightful; too often, victims of war have been portrayed as non-Japanese, when in fact there are countless Japanese whose lives were either disrupted or destroyed by World War II, especially by the twin US atomic bombs that decimated their cities. Yet it is deeply troubling that not a single one of the characters acknowledges their side’s role in the war in the first place and how all of it could equally, and perhaps even more completely, been avoided if the Japanese army had not possessed such imperialistic ambitions at the outset; in fact, Suzu even rails the army for surrendering when she hears of it on the radio, questioning why they had not kept true to their word to ‘fight until the very last man standing’. One could of course argue that she meant that cynically, but the truth is that it isn’t entirely clear if she did not intend it literally. It isn’t quite that we are expecting some form of apology, but the undeniable undertones in painting the Japanese as victims is deeply troubling to say the least.

And it is for that reason that we refuse to embrace Katabuchi’s admirable but politically disquieting anime. It isn’t that it is somewhat languid and narratively lethargic, even though we’re sure mainstream audiences who embraced ‘Your Name’ will probably find it so. It is more that what happens in Suzu’s corner of the world ignores the reality in other parts of the world, i.e. that there were countless others who suffered, even more needlessly, when the Japanese had invaded and bombed their land, before the rest of the world united behind the US in ending the war decisively and resolutely. As beguiling and appealing as its animation may be and portrait of rustic civilian life in the 1940s may be, there is simply no way to love it wholeheartedly when you realise that it may simply be subtly manipulating your emotions to rewrite the narrative on Japanese WWII aggression.

Movie Rating:

(Beautiful and beguiling as its pastoral tale of life in Japan before, during and after World War II may be, the undeniable political undertones in Sunao Katabuchi’s anime will leave you wary, and even disturbed)

Review by Gabriel Chong

You might also like:

Movie Stills